The American Revolution was sparked in part by unjust taxation. After all, the colonists in Boston rebelled against Britain for imposing “taxation without representation,” and summarily tossed English tea into the harbor in protest in 1773.

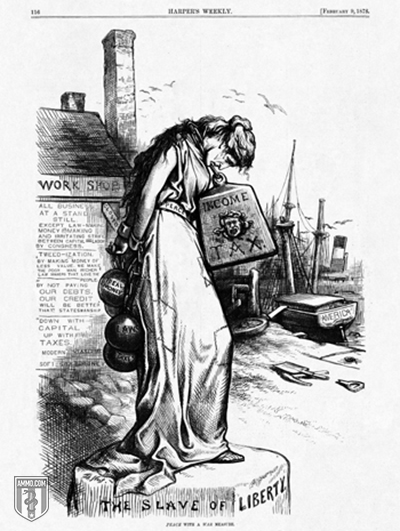

Nowadays Americans collectively spend more than 6 billion hours each year filling out tax forms, keeping records, and learning new tax rules according to the Office of Management and Budget. Complying with the byzantine U.S. tax code is estimated to cost the American economy hundreds of billions of dollars annually – time and money that could otherwise be used for more productive activities like entrepreneurship and investment, or just more family and leisure time.

The majority of these six billion hours sacrificed by Americans to Washington each year goes to complying with a tax that didn’t even exist until 100 years ago – the federal income tax.

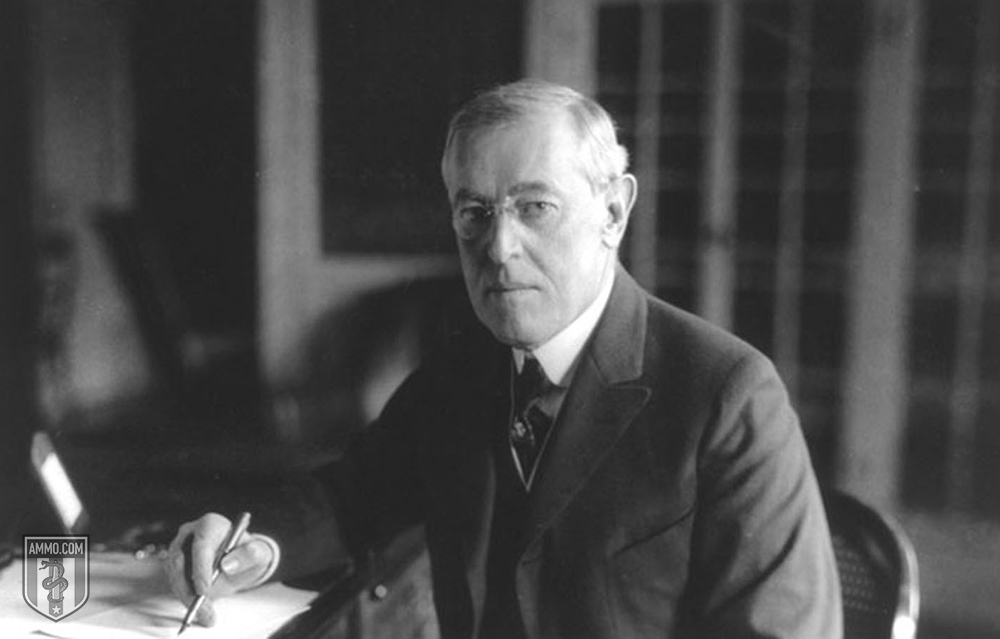

Worse still, this tax has become a political weapon for Washington to incentivize certain activities (home ownership, charitable giving, etc.) and to punish others. It’s a tax that follows Americans wherever they go in the world, and it’s one that was originally sold to the American people by President Woodrow Wilson as a means of “soaking the rich” during the so-called Gilded Age.

How did a country that was founded on the concept of limited government come to embrace such a draconian policy? And what does it say about Washington that tax reform has become synonymous with class warfare and corporate lobbyists?

Read on to learn the history of the 16th Amendment – which authorized the federal collection of an income tax – and how that power has ultimately meant the growth of Washington at the expense of just about everyone else.

Early Attempts to Implement an Income Tax

Could you imagine a time in the U.S. when roads were being paved, there was zero national debt, and the federal government was completely operational – all without income taxes? This may sound like a Libertarian fantasy, but it’s actually an image of the America of yesteryear. Before the advent of the income tax, the U.S. government relied exclusively on tariffs and user fees to finance operations.

Unsurprisingly, operations were much smaller compared with today’s extravagant government programs like welfare, social security, and subsidies. But even though spending was more conservative during the Republic’s early years, certain political events motivated the government to consider more direct ways of reaching into the pockets of its citizens.

One of these political events was the War of 1812. This war may have inspired Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner” as he famously watched the rockets red glare over Fort McHenry, but it was also straining our fiscal resources and the war effort needed to be financed.

Enter the idea of a progressive income tax – based on the British Tax Act of 1798 (which should have been our first warning). Fortunately for the time, the War of 1812 came to a close in 1815, and the discussion of enacting an income tax was tabled for the next few decades.

Ever so stubborn, progressive individuals were hell-bent on enacting income taxes, and they eventually found a way to do this at a local and state level. In time, they would reignite a new movement for the adoption of the federal income tax.

State Versions of the Income Tax

With state governments increasingly embarking on public infrastructure projects and introducing compulsory public education, the money for these programs had to come from somewhere. For the income tax advocates whose hopes were dashed during the War of 1812, state income taxes served as a consolation prize. In turn, income tax supporters immediately got to work and started to chip away at state legislatures.

In the mid-19th century, the fruits of the income tax crowd’s labor began to pay off as several states got the ball rolling. Some of these states included:

- Pennsylvania: 1840 to 1871

- Maryland: 1841 to 1850

- Alabama: 1843 to 1884

- Virginia: 1843 to 1926 (later replaced with a modern individual income tax)

- Florida: 1845 to 1855

- North Carolina: 1849 to 1921 (later replaced with a modern individual income tax)

Slow but sure, income taxes started to make their way from one state legislature to the next. But once the 1860s arrived, income taxes got a tremendous push from one of the most destructive and pivotal events in U.S. history.

Did the income tax supporters finally get their wish?

The Civil War’s Boost for a Federal Income Tax

To say the U.S. was divided during the 1860s would be an understatement.

Ripped apart at the seams by a bloody Civil War (1861-1865), the Union government was desperate for funds to finance its ambitious quest to restore order to the beleaguered nation. Like the War of 1812, proposals for income tax were on the menu. Unlike the preceding war period, however, the U.S. was able to successfully enact an income tax.

Abraham Lincoln signed the Revenue Act of 1861 as a means to finance the expensive war effort. This was followed up with other measures like the Revenue Act of 1862 and Revenue Act of 1864, which created the nation’s first progressive income tax system and the precursor to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

What seemed like a monumental victory for income tax supporters who hoped for a long-lasting income tax system would vanish into the ether once the Civil War ended. No longer needing a massive army to put down rebels and stitch the country back together, the U.S. government let Civil War era income taxes expire once Reconstruction was in full swing. The pro-income tax crowd would have to reassess its tactics and look at other avenues for political change.

The American People Push Back

How did the U.S. government go from embracing massive government expansions during the Civil War to later reverting back to its Constitutional roots of limited government during the next decade? Was it benevolent politicians who, in an act of political kindness, decided to hit the reset button and give Americans their cherished rights back? Or was there something else at play?

Upon further inspection, there is reason to believe that taxes in the 19th century tended to be temporary in nature given the American people’s ideological propensities. Most people were still skeptical of government overreach, especially during the Civil War – a time where habeas corpus was suspended, and the first income tax was implemented. Shell-shocked from a horrific experience that laid waste to countless urban centers and left hundreds of thousands of Americans dead, the American populace wanted a return to normalcy. And that meant scaling back government as much as possible.

Even Henry Ward Beecher, the brother of the famous author Harriet Beecher Stowe, was skeptical of the Radical Republicans’ zealous plans to grow government during the Reconstruction period. Historian Tom Woods in The Politically Incorrect Guide to American History exposed Beecher’s thoughts on the matter:

“The federal government is unfit to exercise minor police and local government, and will inevitably blunder when it attempts it…To oblige the central authority to govern half the territory of the Union by federal civil officers and by the army, is a policy not only uncongenial to our ideas and principles, but pre-eminently dangerous to the spirit of our government.”

Many Americans would agree with Stowe’s assessment – above all, members of Congress who sought to reassert Congressional dominance throughout the rest of the 19th century. But with the arrival of the Progressive Era, the rules of the political game began to change. Soon, ideas of expansive government, which were routinely scoffed at by intellectuals, politicians, and the American population at large throughout the first half of the 19th century, made a fierce comeback during the latter half of the 19th century.

This time around, these ideas began to have considerable staying power.

The Income Tax: A Child of the Progressive Era

Decades of legislative pressure and constant hand-wringing finally began to pay off for income tax supporters.The arrival of the Progressive Era was like Christmas for political figures in favor of an activist state. This was a time when reformers actively pushed for an energetic government to solve all of society’s ills, most notably poverty and income inequality.

Although they were shut out from the federal government throughout the Gilded Age, Progressives focused their attention on local and state races. Additionally, academia became more receptive to the technocratic message of Progressivism, as numerous academics like John Dewey gained prominence during this period and made progressive ideas popular in the Ivory Tower circles.

Many will scoff and think that Ivory Tower ideas have no impact in changing, that these ideas are simply too dense and inaccessible to the masses. However, free market economists like Nobel laureate F.A. Hayek understood the indispensable role ideas play in politics. In his work, The Intellectuals and Socialism, Hayek argued that when certain ideas promoting activist government become prominent among the academia and general culture, they eventually consume the political class whole.

The idea of an income tax would have been laughed out the venue in previous decades. But in the 1890s, it was all the rage at universities throughout the U.S. Soon, political winds started to blow in a more favorable direction.

For a brief moment, Progressives got their wish when the Congress introduced an income tax during the mid-1890s. The Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act, which had an income tax provision attached to it, gained the ire of then President Grover Cleveland for its last-minute amendments. Nevertheless, the Wilson-Gorman Act became law without Cleveland’s signature. The Supreme Court would later strike down the income tax provisions of the Wilson-Gorman Act in 1895’s Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan Trust Co. case.

The Supreme Court’s rejection of the income tax was no trivial failure. It was the first step in starting the conversation on the need for an income tax. Progressives now smelled blood in the water and would come back with a vengeance in less than two decades.

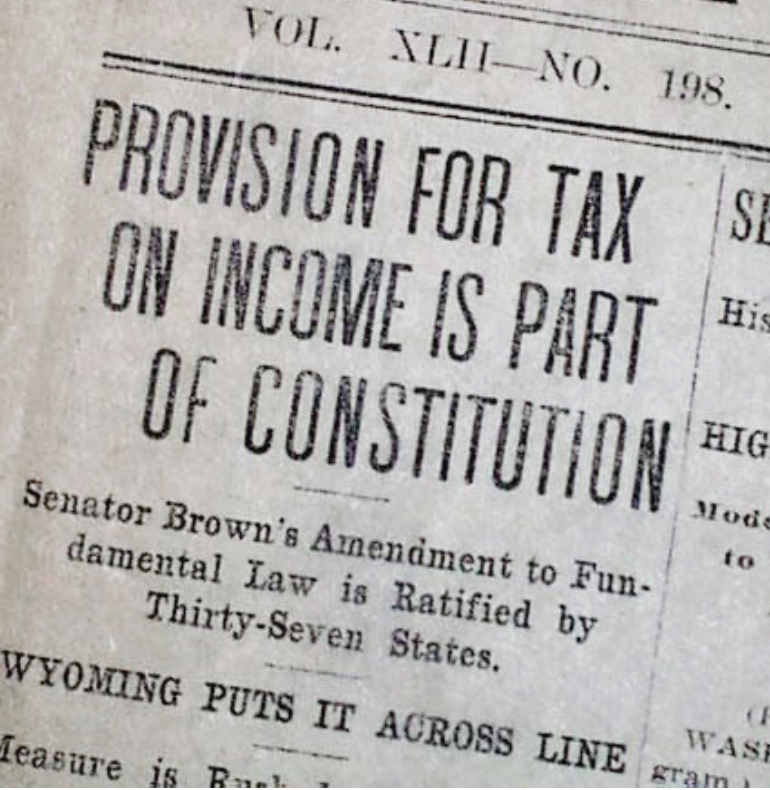

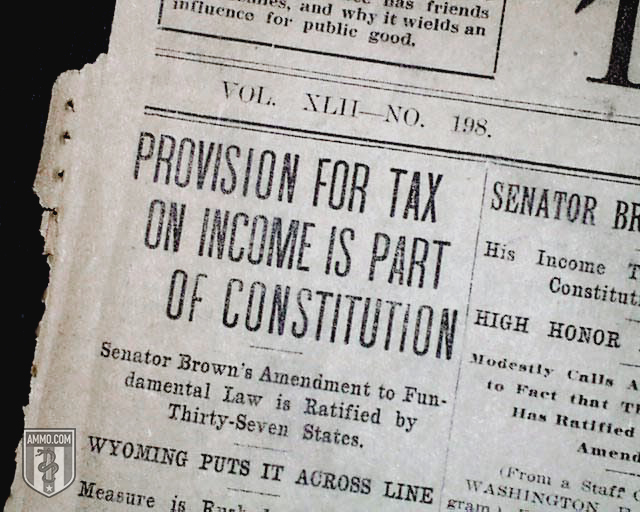

Enter the Wilson Presidency

Not letting the temporary setback of the Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan Trust Co. deter their activism, Progressives continued plowing ahead and making their ideas more palatable to the political class and the masses. Progressivism reached its zenith during the administration of Woodrow Wilson, when progressive reformers finally got their wish as the 16th Amendment was ratified in 1913. This ratification settled any constitutional questions about the legality of this controversial tax. It started out as a relatively limited tax, with individuals making below $20,000 paying a rate of one percent, and the rich – those making making more than $500,000 – paying a seven-percent tax.

Supporters of the income tax sold it as a tax that would only target the filthy rich. But as history has shown, government encroachments have a tendency of growing over time. In 1917, the lowest tax bracket paid two percent, although the highest income earners saw their taxes skyrocket to 67 percent.

At the time, politicians reassured their constituents that those rates would not be permanent and they would eventually be scaled back. Little did taxpayers know what the 1930s and 1940s had in store for them.

The Income Tax: A Normal Part of Public Policy

Since its ratification, the income tax has been a calling card for politicians keen on growing the size of the State. By soaking the rich and redistributing their wealth, politicians can claim to be champions of the common man, all while consolidating their power in D.C. However, economic realities and political backlash have constrained politicians’ abilities to indefinitely raise taxes.

Power-hungry politicians needed a little bit of outside help to make their wildest fantasies become reality. That help usually comes in the form of political crisis, which politicians exploited in its fullest.

The New Deal was the first era that witnessed income taxes rise at astronomical rates. On the eve of the 1929 stock market crash, the highest income earners paid a marginal tax rate of 25 percent. But once the Great Depression was well underway in the mid-1930s, the top tax bracket was paying 63 percent, and the United States’ entrance into World War II catapulted these rates toward 94 percent.

Certain political practices, such as the abandonment of the use of war bonds – debt securities the government issued to finance war efforts – changed certain political realities for the political class. The discontinued use of war bonds made using the income tax and deficit spending a necessity. This was the result of the populace starting to grow skeptical of military action abroad. With war bonds out of the picture, the U.S. relied more on income taxation and central banking to finance military actions and domestic programs after World War II.

Like an annoying chore, the income tax soon became a part of the average American’s life, whether they liked it or not. For some Americans, the rabbit hole of inconveniences and frustration goes even deeper.

Extraterritorial Taxation: The Income Tax’s Worst Kept Secret

Living in foreign lands is one of the most tantalizing experiences for people all over the globe. And after decades of hard work and meticulous saving, many Americans dream of living abroad.

Often times, unsavory political situations like economic collapses, heavy taxation, and even war compel people to search for greener pastures. For many, settling in new lands is a form of wiping the slate clean – disassociating with a tyrannical homeland and starting a new life in a land of opportunities.

But for Americans abroad, the U.S. government still finds a way of sneaking back into their lives. Like an unwanted guest, the income tax has latches on to Americans and follows them all the way to their new place of residency. Thinking that their foreign villa by the beach is a refuge from potential U.S. government meddling, many Americans are caught by surprise when the tax bill comes at their U.S. embassy.

A particularly unique feature of America’s income tax system is its power to tax extraterritorial income. In other words, Americans living abroad are subject to a worldwide tax on their income. One caveat is that American taxpayers enjoy a foreign earned income exclusion that reduces their overall tax burden. As of 2018, the maximum exclusion for taxpayers is $103,900. Nevertheless, the U.S. and Eritrea are unique in their extraterritorial taxation models. Eritrea, however, taxes its citizens living overseas at a flat rate of two percent.

The extraterritorial nature of U.S. taxes has not been without its fair share of legal controversies. George Cook, an American living in Mexico for 20 years, was perturbed by the fact that he had to pay an income tax on his foreign earnings despite no longer having ties with his country of origin. George’s dispute eventually made its way to the Supreme Court in 1924, and the issue was resolved in the Supreme Court case Cook v. Tait.

The Supreme Court ended up ruling that international taxation of foreign income was constitutional because the U.S. government “benefits its citizens and their property” wherever they live. In essence, Americans are double taxed – they must pay both the taxes in their new country of residence and American income taxes.

Still not satisfied, D.C. has made sure to extend its international taxation reach by passing the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) in 2010. FATCA essentially turns banks and financial institutions into de facto enforcement branches of the IRS.

Although FATCA is an American law, foreign countries must comply with its ordinances. FATCA initially requires that all foreign financial institutions register with the IRS. In the case that foreign financial institutions don’t follow through with FATCA standards, the U.S. government can levy a withholding tax of 30 percent on the foreign bank’s earnings.

The Sneakiness of Income Tax Withholding

One of the sneakiest aspects of the income tax is the practice of withholding. Instead of paying a lump sum on April 15th, most taxpayers have their income taxes deducted from their paycheck. Their employer essentially becomes an unpaid tax collector that gradually extracts their income in relative silence.

Come Tax Day, many Americans receive money back after paying excess taxes all year, so they’re left feeling like they’ve been given the gift of free money. Sounds too good to be true, right? Skeptics have every reason to question the euphoria certain Americans display on April 15th. In reality, the government is actually forcing taxpayers to loan it money to finance lavish programs, with zero interest.

Ironically enough, withholding wasn’t an original feature of the income tax. It wasn’t until World War II that the practice of tax withholding was standardized through the Current Tax Payment Act of 1943. Withholding would later become a permanent feature of the current tax code, despite its original intentions of being a temporary wartime measure.

Sales Tax Deductions vs. Income Tax Deductions

Though the income tax is a convoluted maze that creates headaches for business owners and individual taxpayers alike, there are certain features in the current tax code that can be used to help taxpayers reduce their overall tax burden and make their tax filing experience more comfortable. Tax deductions are just one of these features.

Taxpayers have the choice of opting for a standard deduction or they can itemize their deductions. If an individual decides to itemize, one of the deductions they’re allowed to take is on various taxes at the state and local level. These deductions are called SALT deductions. Taking a sales tax deduction is a legitimate way to recoup an individual’s local and state sales tax obligations

For 2018, the standard tax deduction was $12,000 for individuals, $18,000 for heads of household, and $24,000 for married couples filing together. Itemizing is a reasonable route to go if an individual’s itemized deductions are larger than the allowed standard deduction. Individuals can’t deduct all state and local taxes, however. They have to choose between deducting state sales taxes or state income taxes, but they can’t deduct both. That being said, taxpayers can deduct state and local property taxes irrespective of the options they choose.

It should be noted that this deduction strategy is not necessarily a one-way ticket to lower taxes. In the case that itemizing deductions gives an individual a lower income tax burden than a standard deduction, the sales tax deduction is worth looking into. It makes sense for individuals who have realized major purchases, thus paying a considerable amount in sales taxes, or for those living in states with no income tax, to include the sales tax in their list of itemized deductions.

Bear in mind that certain things have changed since the 2017 tax reforms. The Trump administration’s tax reforms have capped how much individuals can deduct from federal income taxes for state and local income, property, and sales taxes. Under the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, taxpayers can only deduct a maximum of $10,000 in state income taxes and property taxes combined.

The IRS Sales Tax Deduction Calculator

For those who proceed to file a Form 1040 and itemize deductions on Schedule A, they have the option of choosing between claiming state and local income taxes or state and local sales taxes.

If an individual is planning to claim sales taxes paid in order to lower their federal income tax burden, they should first go to the IRS’ Sales Tax Deduction Calculator page. This way they can better estimate their itemized SALT tax savings versus taking the standard deduction.

The IRS’ Sales Tax Deduction Calculator is a handy tool for helping individuals figure out the amount of state and local sales tax one can claim. This is true even if the individual’s state and local sales tax rates changed during the year (e.g., because the rates changed or because you moved your personal residence). Be sure and have your Form 1040 draft in-hand when you are ready to calculate.

GILTI: The Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income Provision

Apart from lowering certain taxes, the 2017 Trump tax reforms came with a series of changes with global implications to the U.S. tax code. One that stands out in particular is the introduction of “The Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income” (which is subversively-nicknamed “GILTI”). GILTI is a new tax provision that specifically targets U.S. corporations that own Controlled Foreign Companies (CFCs) for U.S. tax purposes.

Prior to GILTI, U.S. corporations with a CFC could defer U.S. taxes on the earnings of their CFCs until the CFC distributed those earnings to the parent U.S. corporation. (This is how a U.S.-based multinational like Apple Inc. came to have close to a quarter trillion dollars of foreign cash on-hand, and subsequently had to explain American tax law to U.S. Senators who couldn’t understand what Apple was in fact legally doing.) Post-GILTI, U.S. corporations are taxed at a rate of 10.5% on the earnings of their CFCs regardless of whether the earnings are distributed or not.

To address this transition, the U.S. made two important changes. First, the law authorized the IRS to impose a Section 965 transition tax (also called “The Mandatory Repatriation Tax”) on the accumulated earnings of CFCs through the end of 2017. And second, the law authorized the IRS to impose on CFCs the aforementioned GILTI tax on all future (i.e., post-2017) foreign earnings.

In practice, here’s how the GILTI tax works: Assume you have a CFC owned by a U.S. C corporation (like Apple Inc.) with $1,000 in earnings for 2019. Also assume it has tangible assets with a tax basis of $2,000. You would subtract $200 (10% of $2,000 tangible assets) from the $1,000 in earnings, leaving you with $800 to which a 10.5% tax rate is applied – and you’d get a GILTI tax due of $84.

Amongst Constitutional scholars, the Section 965 transition tax has raised 5th Amendment due process concerns because it authorizes the IRS to impose a retroactive tax on foreign earnings nearly three decades after the fact. To comply with this change, companies have the option to pay in installments over eight years – but they still owe back taxes worth 15.5% on overseas profits computed under U.S. tax principles represented by cash and liquid assets, and 8% on profits represented by illiquid assets.

It is this illiquid asset provision which is ensnaring some expected U.S. companies like Kansas City Southern and Tupperware (hardly Silicon Valley darlings like Apple Inc.), and causing them to pay taxes above the new statutory corporate rate of 21%. And in other cases, business owners must resort to becoming residents of the foreign country their multinational is operating in as a means of lowering their tax burden. This is on display when people consider establishing their residency in Puerto Rico, as will be discussed below.

Tax Reformers Still Have Work to Do

Despite the marketing campaign that initially sold the income tax as a straightforward measure to finance government, it has morphed into a legal maze that keeps tax lawyers gainfully employed. After more than a century in existence, the income tax may no longer be worth the headache that millions of Americans must cope with every year on April 15th.

Although the last few decades have witnessed politicians reducing income taxes at reasonable rates, fiscal irresponsibility and a lopsided tax burden remain lingering problems.

As of 2018, the U.S. has been running a fiscal deficit of $778 billion, in a year when unemployment has reached historical lows. One can only imagine how deep those deficits will go under less favorable economic circumstances. A report from the Wall Street Journal also indicates that the U.S. income tax system remains very progressive, with the top 20 percent of taxpayers paying 87 percent of total income tax revenue.

Tax cuts are not bad in of themselves. The great Libertarian economist Milton Friedman was in “favor of cutting taxes under any circumstances and for any excuse, for any reason, whenever it’s possible.” The real problem at hand is the political class’s insistence on maintaining unsustainable levels of spending

In a tragic twist of fate, these deficits will negate all of the positive effects of the original tax cuts. As debt accumulates, future generations will be stuck with a hefty tax bill. Not only that, but big spending crowds out private-sector investment, thus creating a capital-starved future economy. History has shown, in such cases of fiscal irresponsibility, that governments will either raise taxes exorbitantly or turn to the printing presses to debase the currency.

Alternative Tax Models to Consider

For many Americans today, the idea of a world without income taxes seems almost absurd. Income tax has become a presence like furniture in the living room – a baseline they’ve been so used to that they no longer even notice it. But for many business owners, the income tax is a very real part of everyday life that must be dealt with, lest they want to suffer legal penalties.

In the frustrated business owner’s eyes, any type of reform to simplify the tax code would be a release from the current income tax quagmire. The good news is that business owners no longer have to figure out alternatives to the present tax code. There are numerous individuals who have stepped up to plate and put forward reasonable alternatives to the current system.

Several proposals to reform the income tax have come in the form of a national sales tax or a flat tax. Both of these taxes are preferable to the income tax status quo. A flat tax entails having a single tax that taxes every American at one rate. Additionally, the flat tax treats all taxpayers and income equally, in stark contrast to the current tax model.

On the other hand, the national sales tax would repeal the current income tax code and replace it with a tax on the final sale of all goods and services to consumers. Although the most notable difference between the national sales and flat tax is the collection point, they are actually quite similar when it comes to how income is treated.

Economist Dan Mitchell breaks down some of the similarities between the flat tax and a national sales tax:

“A single flat rate. Under both plans, income is taxed at one low rate. This would ensure that the government treated taxpayers equally and would address the problem of high marginal tax rates. The single low rate also would promote faster economic growth by minimizing tax penalties on work, risk-taking, and entrepreneurship.”

“No bias against savings and investment. Implementing either the flat tax or a national sales tax would eliminate the current tax code’s bias against capital formation by ensuring that no income is taxed more than one time. Because double taxation of capital income is a pervasive problem in the current law, going to the flat tax or a national sales tax would stimulate higher incomes and faster growth by minimizing the tax penalties on savings and investment.”

“Equality. Adoption of the flat tax or a national sales tax also would end the discriminatory treatment caused by a tax code that grants preferences or imposes penalties on certain behaviors and activities. Either reform would change the code so that all taxpayers – and all income – are treated the same under the law.”

Mitchell is correct in his assessment that the current progressive system punishes success and discourages saving and investment – two of the pillars of capital accumulation. In addition, risk-taking and entrepreneurship are crucial in a market economy. Progressive income taxes impede this process through its arbitrary redistributions on income.

In the same token, income taxes do have a social engineering function that encourages certain types of behavior and favors certain interest groups over others. For example, on the class warrior side of the aisle, the earned-income tax credit effectively subsidizes low-income tax filers. Other uses of the tax code to socially engineer desired results include sweetheart tax breaks for the solar industry or making childcare costs deductible.

All in all, a switch to either a national sales tax or a flat tax would lead to a simpler tax system that no longer incentivizes interest group politicking or places a disproportionate tax burden on a certain class of taxpayers. Instead, they would encourage productive activities like entrepreneurship, saving, and investment.

Puerto Rico: Tax Incentives For Americans

Due to GILTI and other questionable features of the U.S. tax code, Americans have looked for ways to move abroad so as to lighten their tax burden. The U.S. is unique in its approach to taxing worldwide income, which makes it very difficult for Americans to substantially reduce the amount of taxes they are paying to the U.S. government, even if they live abroad.

With the recent Trump tax reforms, it has become more difficult for U.S. citizens to lower their global tax burden, however, there are still ways around this. One of these strategies has been to move to U.S. territories, which are not subject to the U.S. income tax.

One of the more popular destinations for Americans looking for favorable tax advantages is Puerto Rico. Provided that they they do their homework, Americans could potentially enjoy federal income tax exemptions and see their taxes drop by 90%.

Two programs that the Puerto Rican government offers are Act 20 and Act 22, which are the island’s two major tax incentives.

Here is a brief summary of what these programs entail:

Act 20: The Export Services Act

Act 20 targets certain types of qualifying businesses, like consulting or financial services, by offering incentives such as 4% corporate income tax rates. This is available to corporations who relocate to Puerto Rico and meet the following requirements:

- Become a bona fide resident. In other words, an individual must relocate their center of life to the island and spend at least half the year (183 days) in Puerto Rico.

- Set up a Puerto Rican company.

- Establish an office in the country.

For Americans, GILTI has changed the tax outlook in Puerto Rico. Now that corporate tax policy has been streamlined for all CFCs, U.S persons will have to pay another 6.5% in corporate taxes to meet the GILTI minimum of 10.5%. The best way for Americans who have a CFC to deal with this provision is by becoming official residents of Puerto Rico.

Act 22: Individual Investor Act

Act 22, the Individual Investors Act, gives investors the ability to pay 0% tax on interest, dividends, and capital gains while living in Puerto Rico as a certified resident. Like Act 20, the taxpayer must be a bona fide resident who has relocated their life to Puerto Rico and must spend at least half the year (183 days) on the island.

This program is especially attractive to traders and crypto-investors, or any individual with a large amount of passive income or capital gains from any source.

A Cause for Hope

The tedious process of filing tax returns is a common pain point for millions of Americans on April 15th. After more than a century’s existence, the income tax has become a political baseline, which many Americans take as a given.

Make no mistake about it, the income tax is no mundane feature of the American political economy. In fact, it’s one of the largest enablers of government growth. To genuinely reduce the size of the American state in economic affairs, the abolition of the income tax – or at the very least, a gradual phase-out – would be solid steps in bringing fiscal sanity.

Thanks to a few high-profile political campaigns over the last decade, the desire to get rid of the income tax is no fringe idea, and is starting to gain momentum in Conservative and Libertarian circles.

Since 2008, each presidential cycle has featured candidates on the Republican side of the aisle with campaigns to abolish the IRS. Ron Paul did so in 2008 and 2012, whereas candidates like Paul’s son Rand Paul and Senator Ted Cruz followed in the retired Congressman’s footsteps during the 2016 Republican primaries.

Should the Overton window of public opinion shift toward limited government, the days of Americans having to deal with the IRS may soon come to an end.

After all, tax rebellions are in the American people’s DNA. And with the U.S.’s fiscal situation deteriorating annually, bold measures will need to be taken.

Reproduced from ammo.com with permission. Original can be viewed here.